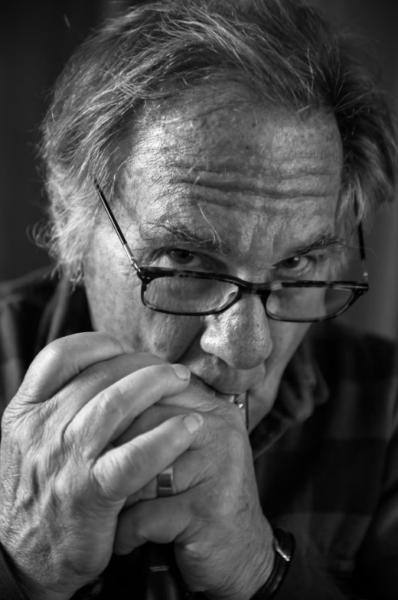

Larry Fink, 1941 – 2023: In Memoriam

We are very sad to hear about the passing of our close friend Larry Fink. The photographer and educator passed peacefully in his home in Pennsylvania on November 25th, 2023. powerHouse Books will miss him dearly.

We are very sad to hear about the passing of our close friend Larry Fink. The photographer and educator passed peacefully in his home in Pennsylvania on November 25th, 2023. powerHouse Books will miss him dearly.

A Moment With Larry Fink, NYT, 2011

A Fond Farewell to Photographer Larry Fink, 82, Vanity Fair, 2023

Larry Fink, photographer who explored class divides, dies at 82, The Washington Post, 2023

Some notes from powerHouse Books founder and publisher, Daniel Power:

Uncle Larry’s book Boxing was the first duotone book we printed in Italy; we went on press with Thomas Palmer’s beautiful duotone seps, Burt Sugar’s incisive history of the beautiful science, and Yolanda Cuomo’s exceptionally empathic design. It was a watershed moment for powerHouse Books. I wept from exhaustion boarding the plane in Venice; I had never been under such pressure to live up to the printing standards of Tom’s and Yolanda’s towering book legacies; we were just two years old, two young guys taking cast offs from Walter Keller (who had his hands full with Robert, Nan, and the other Larry, as in Clark).

Boxing was pulled from his Boxing and Brokers series—incredible, intimate moments of young fighters and their trainers coming up through the local gyms in Pennsylvania and New York, coupled with almost disembodied tableau of Wall Street traders (not bros at that time), all wrapped around land-line cords and framed by paper, nary a computer in sight. Drop the brokers I suggested; Larry paired real power—empathic, brotherly, caring, fierce—with empty power: temporal, shallow, vain, greed-inducing. I got his point, but not his manifesto—the real reason he looked at subjects and people and places the way he did: to distill the beauty, the essence maybe, of a belief system he understood to be valid, admirable—just—and those systems he similarly knew to be false gods, deceiver of men’s good intentions (yes he would include the fairer half in that line, I was just trying to emulate his baseline). This is why his first book Social Graces (our third book with him) cuts so deep: the elegance, the beauty, the shockingly candid moments of his neighbors in Martins Creek, Pennsylvania are imperfectly refracted in the still lifes and frozen moments of isolation and posturing of the city’s high society balls and club socials. It does not take long for the initiated and the novice alike to see where his heart lies.

Our second book with Larry, Runway, was different: this was a showcase only for the stunning artistry of Larry’s vision, his ability to craft a depiction of a world in a single frame. There was no heart in this: Runway is a book of pure art. I think he appreciated being able to not dig down into his soul to highlight a struggle between good and evil, and just show a world he was not from how it could appear, not as a judgemental outsider, but as someone who knew he had the chops to fool us all into thinking he was.

Our last project with him was Forbidden Pictures, which grew out of a Vanity Fair assignment, where Larry’s full political allegiance was front in center. A slim paperback of staged photographs echoing Weimar decadence, the models’ likeness to Bush cabinet members was uncanny and unsettling. Adding some local journalists in the shoot, the entire project was practically an electrical current between studiously composed and abandonly candid images. This was pure mastery on display.

Larry insisted we do a small book of his Beats-era photographs; images he made as a young buck in the city, capturing indelible images of an idealist’s heaven—young people being themselves, jazz poetry, new modes of existence. And people power. Larry was as bedrock as one could be in the power of the people to do what is right in society, if the liars, the cheats, the wealth, the corruption, the injustice could be overthrown. He softened in later years, but do not think for a moment his allegiance waned in the slightest.

Larry’s spirit and manifestos are what is driving our last book with him, one we began talking about shortly after he came to Brooklyn for a new Mike Tyson book we had just published (young Mike is in the Boxing book); he wanted to do a big retrospective; his gallerist Bene Taschen had been suggesting this for a while. Why not get the band back together, I thought; later that spring, there we were at Yo’s garage studio in scenic Weehawken, looking over the hundreds of pages of miniature sequences of images, arranged by table sections by decades: 1950s, 60s, 70s, 80s, 90s, 00s, 10s, even a few 20s. Larry had spent the pandemic digging deep into his archive, maybe reviewing his life (knowing some health concerns were now bearing down hard on him): how in the world had he photographed so much for so long, and the world knowing but a small fraction of three, maybe four bodies of work (besides his spectacular—nay brilliant—association with Grayon Carter’s Vanity Fair for a decade plus? Yolanda could only parrot,”I know, I know,” as those assembled in the studio—Jamie, Jonno, myself, and even Larry—walked from table side to table side, then table to table, mouths agape, stunned at the new images we were seeing, or being familiar with them, stunned at the beauty and artistry of Yo’s poetic assembly of images new to the world and those world famous.

The most creative editing sessions I have ever been part of quickly ensued, and we decided to bring in Larry’s writings (if that is the right word, probably more musings/diatribes/jazz word mind poems are probably more like it), and before we knew it, we had 432 pages of perfection. There is nothing I could have changed, or would want to change. This is the book you have now (or will soon-ish have) in your hands: it is the most perfect photo book I have ever done. With Larry’s life complete, my publishing life now is.

Keep on truckin’ [cue harmonica trill].

Click HERE to learn more about book we were working on at the time of Fink’s passing, out mid 2024.